How Can I Write about India?

How can I, Dianne, write about India? Our “Tips for Travelers” called India “a land of contrasts.” Our professor from India said that we would find it a place of “great contradictions” One book proclaimed that “whatever you said about India, the reverse was also true.” And yet, none of these words prepared us. India did indeed both fascinate and repel. Tom does not want to return. I haven’t yet decided.

First are all the people—people on foot, people on bicycles, people on motorized trishaws, people jammed into buses; people in donkey carts, people in wagons pulled by giant white bulls or water buffalo, people sleeping or dying on the sidewalks or streets. All moving. And then there the are the people who also occupy spaces who are still. Deformed beggars inching legless bodies over the piles of garbage and litter and dirt and broken pieces of concrete and stone that exist next to tall buildings sparkling white and spotless and modern amenities and proclaiming their names of new hi-tech and wealthy companies. Below naked children play in the mud with several mange-ridden dogs as a (sacred) cow ambles across the road, stopping traffic, until it reaches their side and searches through the garbage for something to eat. Next door, a shack is filled with men sitting on plastic stools eating soup or rice and the flies buzz around and cover small plates set out on the rickety tables. And the noise—too many people loudly trying to hustle gum and fruit and taxi rides and tea and plastic bags and small cheap painted Hindu gods. The cranes and big machinery continue to roar and the horns of all the vehicles honk and bong and blow in deafening sound. And the smell…India in most places smells—and is—an open sewer. Men and children openly urinate and defecate and pigs and cows and dogs run free to do the same. And the air, at least in Chennai and Delhi, burns the eyes.

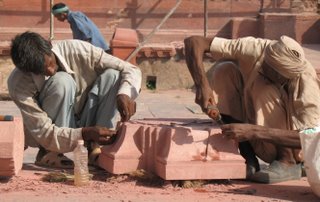

And yet, there are places of extreme beauty as well. The red sandstone abandoned cities that stand on hills and have done so for over a thousand years, like Fatehpur which stands empty now but which once was larger and more populated and civilized than London of the same time.. The marble peacock arches of the Agra Fort, the fort that has never been attacked, the fort that has courtyard after beautiful courtyard with small and large fountains and a marble pool with carved seats so the concubines could coolly amuse themselves, the quarters all decorated with patterned designs, painted, and carved and inlaid sunflowers and geometric designs. And dawn on the Ganges with a huge red sun rising over the water while hundreds bathe on the shores by the temples and burn their dead in huge bonfires and set prayer candles and thousands of flower wreathes to float on the holy water. And the chanting that carries over the sounds of the hucksters that follow the tourists even onto the river.

`

And the Taj Mahal… the memorial of an ancient love story, built by Shah Jahun for his beloved dead wife to fulfill her request that world would always remember her. It is a “wonder of the world” perhaps “the most architecturally perfect” building ever to be completed. The Taj floats creamy white in the late afternoon sky, its massive size disguised by its delicate carving and perfect symmetry, four minarets at each corner slant imperceptibly in case an earthquake should hit—and they will fall away from the building itself. The Taj…like a white fairy-tale castle out of some exotic myth. Looking at it from the beginning of its long stone walkway and reflecting pool, it could almost be an illusion, a miniature, embroidered and carved and inlaid and glowing perfection.

And the people of India, poor and rich, handsome and glowing, the women in beautiful colors refusing to adopt the pallid hues of tan and beiges or the grays and blacks of, the Western world. At the Taj alone women strolled dressed in colorful saris: turquoise and pink; neon green and orange: royal navy and maroon edged in gold; mustard yellow decorated with gold flowers; lavender and peach; saffron over maroon with maroon flowers;; deep teal over saffron yellow: apple green with smudges of sky blue: then three women walking abreast—one in peach, one in deeper orange, one in deep, deep rust; then three more—one all in lemon , one in peach, one in black raspberry—all luscious colors.

Enjoy Tom’s photos—but as wonderful as they are, they can’t begin to capture either the nightmare or the beauty of India.

,